Schizachyrium fragile

(R.Br.) A.Camus

Firegrass, Red Spathe Grass

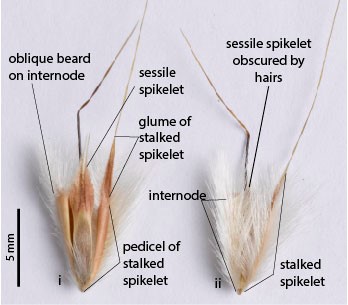

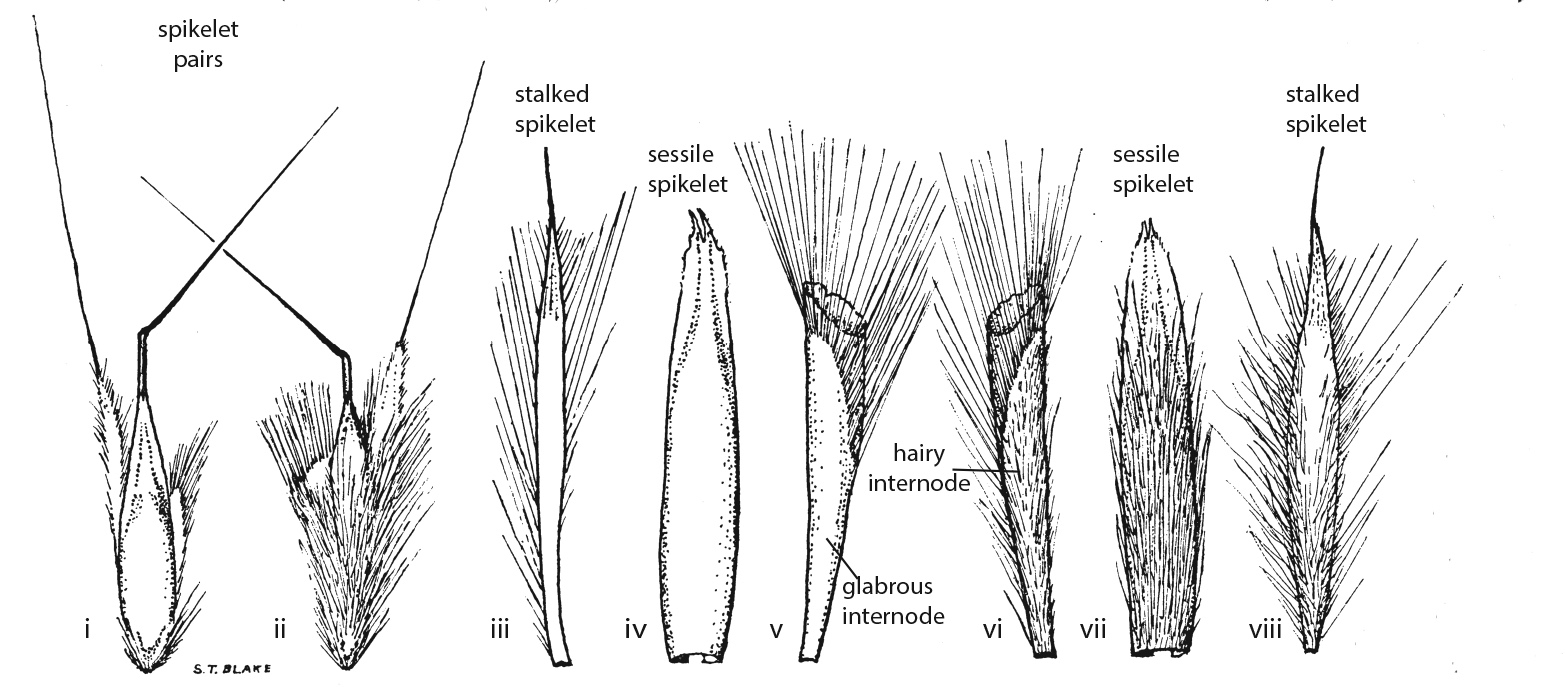

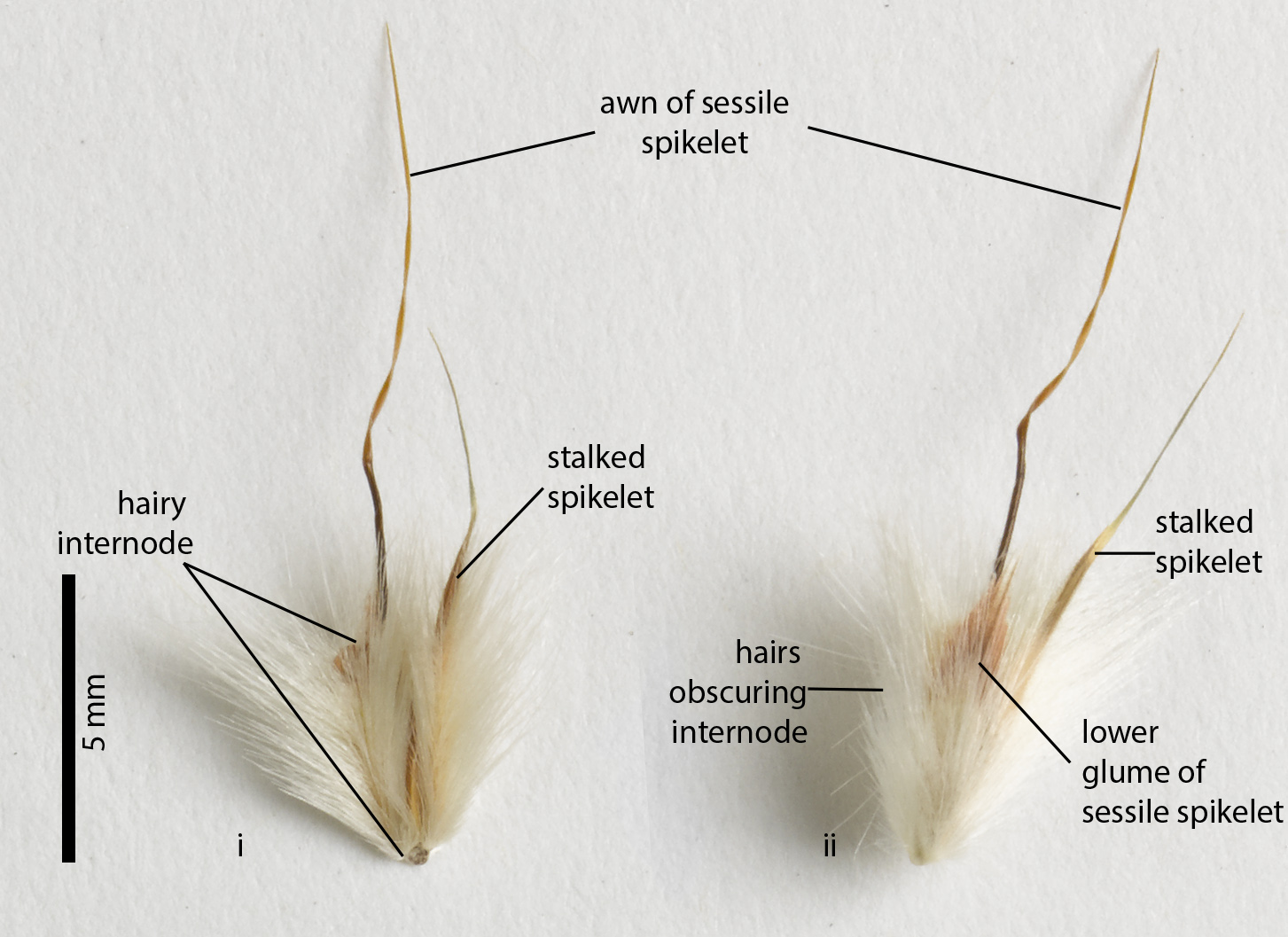

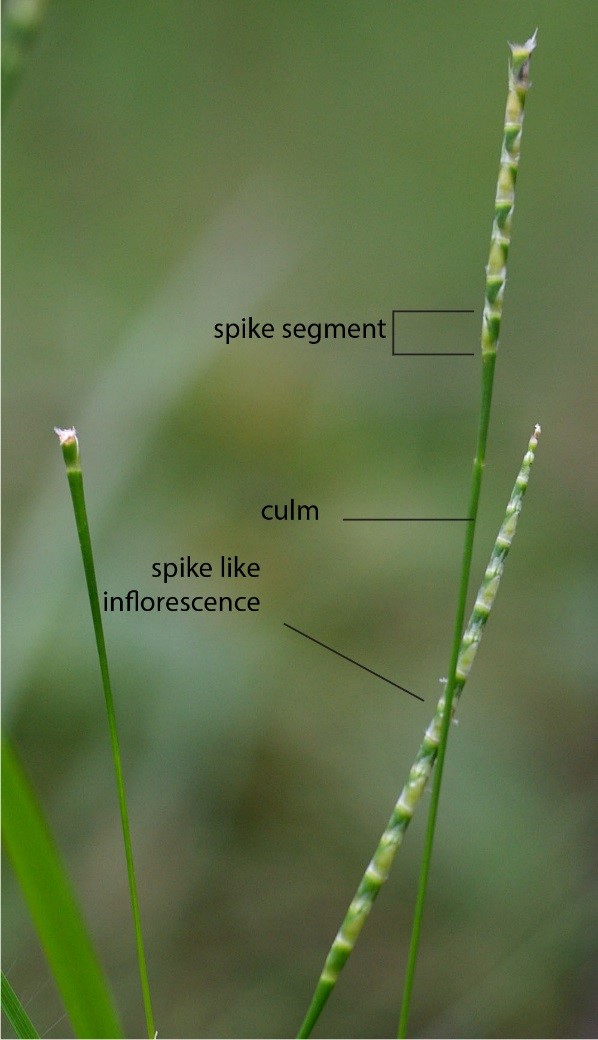

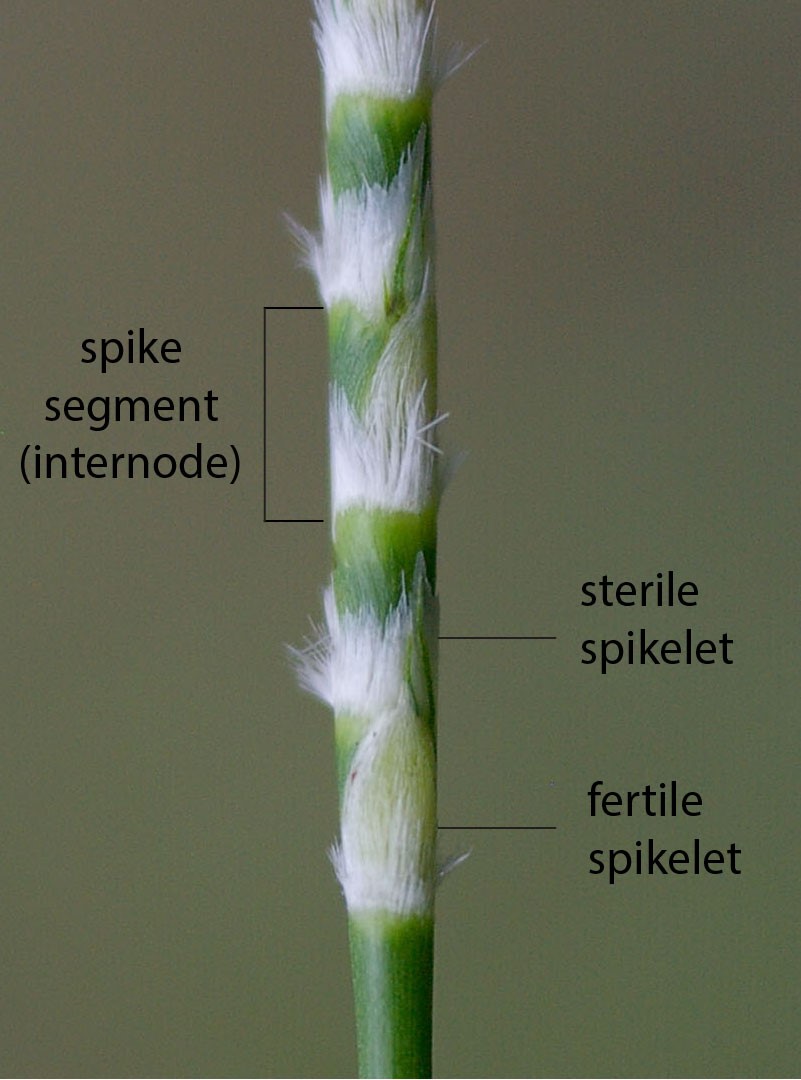

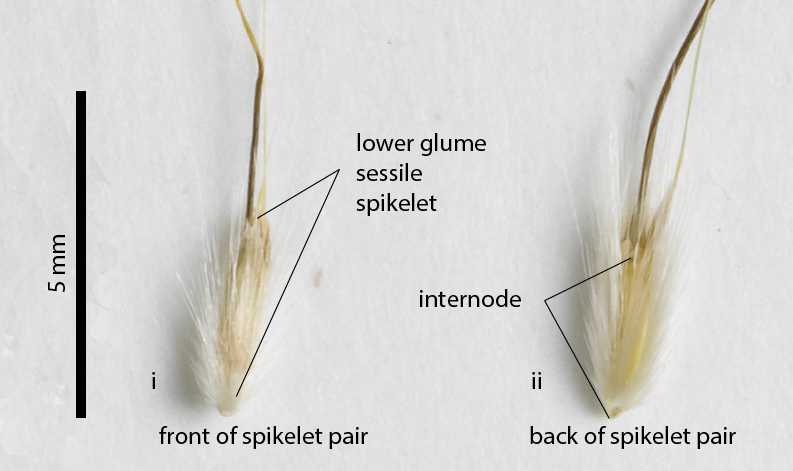

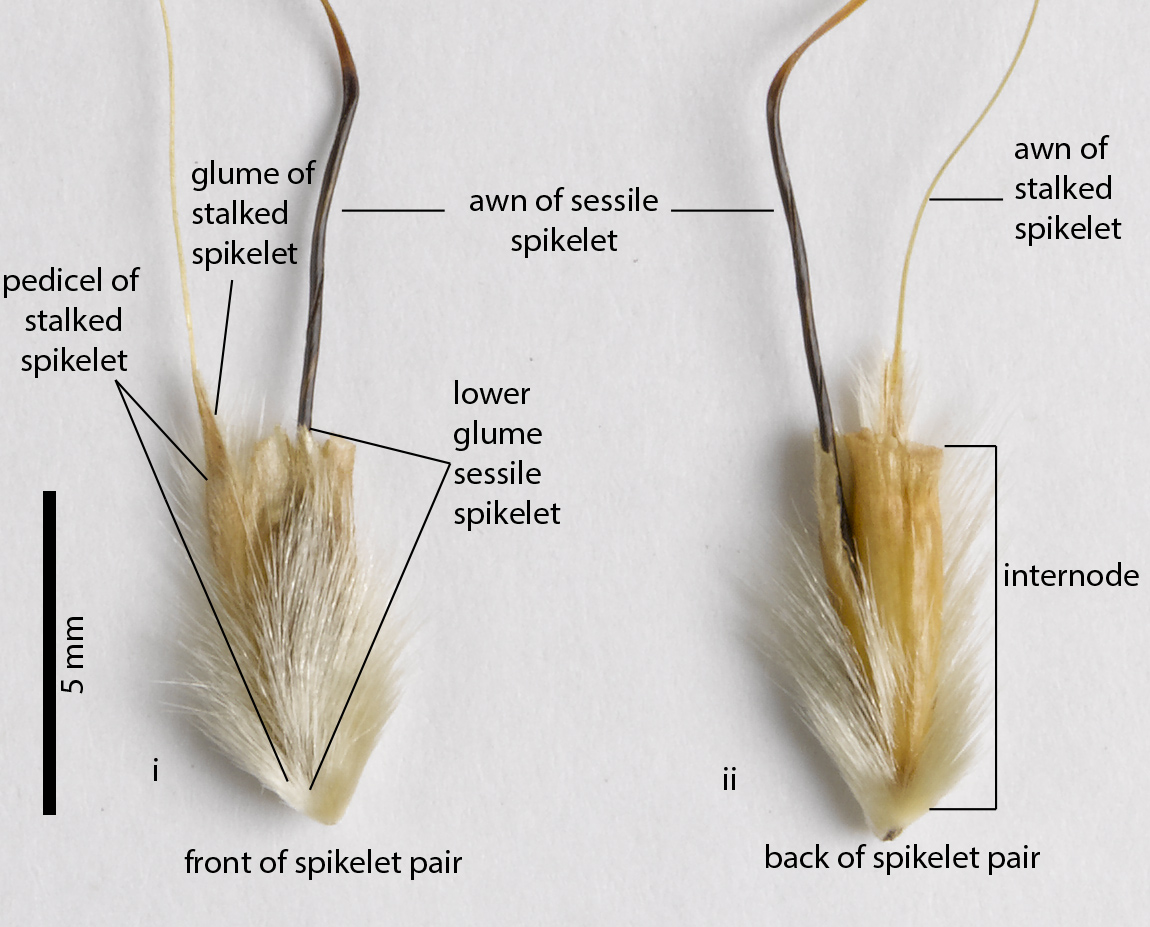

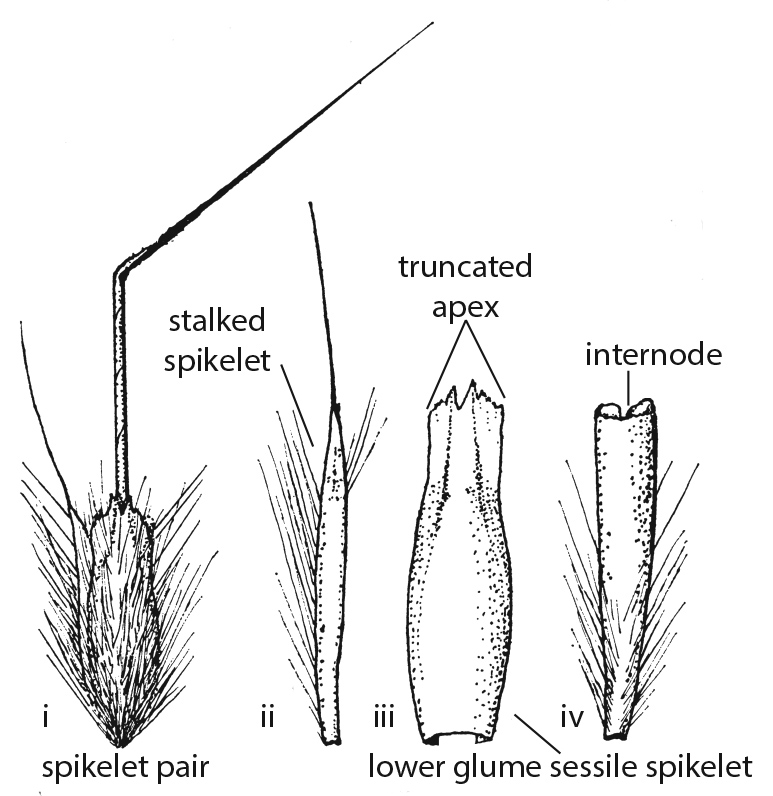

A tufted or single stemmed, slender annual, very common on sandy soils throughout the savanna regions of northern Australia. Plants erect or lying along the ground, 10-75 cm tall, with narrow leaves arising from the base and along the stems (Fig. 1). Leaves, stems and flowers often red-tinged or rusty brown especially when drying out through the dry season. Stems give rise to one or a few separate flowering heads or spikes each enclosed or partially enclosed in a leaf-like sheath (or spatheole) (Fig. 2). The basic flowering units or spikelets are arranged in compact pairs, each pair arranged one after the other in what appears as a solid spike-like flowering head (Fig. 2). The flowering spike becomes fragile with age and breaks apart between the pairs of spikelets (Fig. 3). Each spikelet pair consists of a stalkless spikelet, a stalked spikelet and an internode (a segment of the flowering stem) (Fig. 3 & 4). The internode connects each spikelet pair to the next spikelet on the spike (Fig. 5).The spikelet pairs are clothed in long white hairs making details on the spikelets difficult to see without dissection and magnification. The stalkless spikelet is characterised by a large glume, flattened from front to back, with flaps or wings along the margin that taper into a fine tip (Fig. 3i, 4iv & 4vii, 6ii), it contains 1 fertile floret (a modified grass flower) with a distinct awn or bristle which is bent along a 1/3 to a half of its’ length (Fig.6). The stalked spikelet consists of a single glume only, tapered into a bristle or awn, it is much smaller than the glume on the stalkless spikelet, however it can appear larger as the stalk and glume are generally appear as one structure (Fig. 3i). Be aware that the terminal spikelet cluster occuring at the tip of each flowering spike will often have two stalked spikelets which will not reflect the typical spikelet arrangement described above.

Botanical Description (ATH)

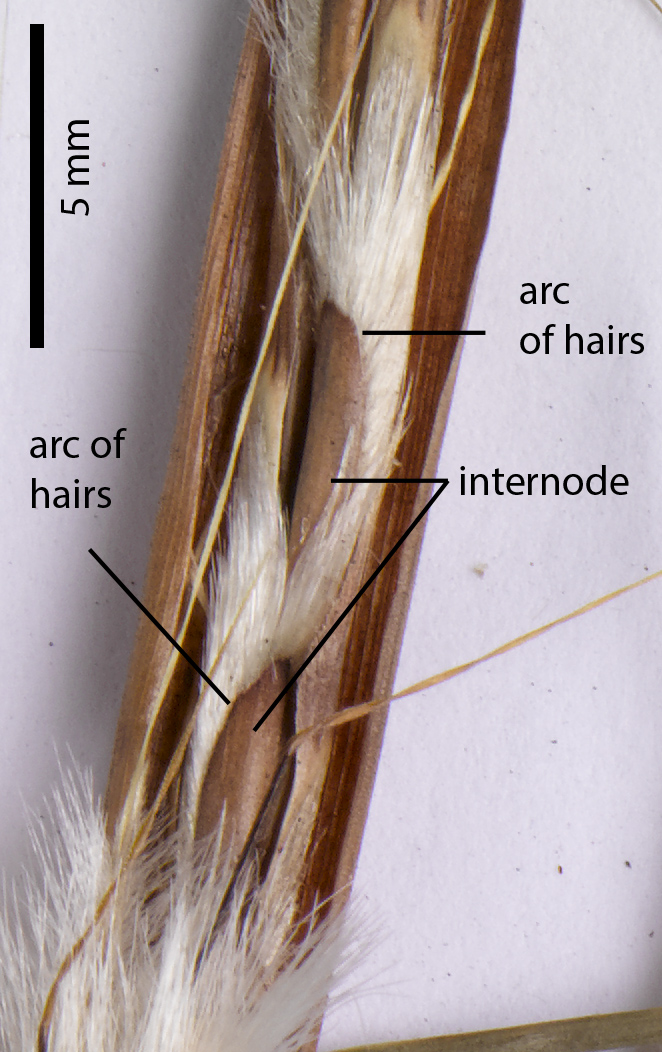

Annual. Culms erect, stature slender to delicate, 10-75 cm tall. Leaf-blades 1-3 mm wide, flat or conduplicate, 2-10 cm long, surface scaberulous. Inflorescence a rame (an unbranched inflorescence in which the main axis produces a series of paired spikelets, one sessile and one pedicellate, the oldest at the base and the youngest at the top), 3-6 cm long, 7-12 jointed (Fig. 2). Rhachis fragile at the nodes. Spikelets partially enclosed in spatheole at maturity (Fig. 2). Sessile spikelets 5-10 mm long, narrowly ovate to oblong, dorsally compressed; lower glume winged, lemma awn 9-15 (-28) mm long (Fig. 3i, 4iv & vii, 6ii). The pedicelled spikelet consists of the lower glume only, the glume 1-3.5 mm long with an awn 1.5-11 (30) mm long, on a stalk longer than the spikelet (Fig. 3i). The rhachis internode typically has an oblique beard or arc of long hairs running along its’ length (Fig. 4v, 5). Usually this arc is quite distinct when most of the internode is glabrous, however, sometimes the arc is obscured by the presence of other hairs on the internode (Fig. 4vi & 6).

Diagnostic Features (ATH)

The slender flowering spikes emerging from a leaf like sheath are characteristic of most Schizachyrium species seen in northern Australia. From a distance the silky or fluffy white flowering spikes of Schizachyrium fragile can be confused with Mnesithea formosa (Fig. 7), however, close examination will show that Mnesithea formosa spikelets have no bristles (are awnless) and are not partially enclosed within a spatheole or leaf like sheath when mature (Fig. 8). Schizachyrium fragile can dominate the ground layer in large patches and is usually reddish brown in colour at maturity. As it is the most common species of Schizachyrium in northern Australia it is the most likely species collectors will encounter.

Distinguishing Schizachyrium fragile from other species in the genus can be difficult as it is a highly variable species and accurate identification requires mature spikelets, dissection of the spikelet pair, attention to detail and magnification with either a hand lens or dissecting microsope. The easiest character for identifying S. fragile is the presence of an oblique beard on the rhachis internode (Fig. 4v, 5), however, this beard can obscured by other hairs in some specimens and therefore is sometimes difficult to recognise (Fig. 4vi & 6). In those instances the species most likely to be confused with S. fragile are Schizachyrium perplexum (Fig. 9 & 10) and Schyizachyrium pachyarthron (Fig. 11 & 12). From S. perplexum it is distinguished by the size of the stalkless (sessile) spikelet, 5-10 mm for S. fragile, 3.5-4.5 mm in S. perplexum. From S. pachyarthron it is is recognised by the shape of the lower glume on the stalkless (sessile) spikelet, strongly tapered in S.fragile (Fig. 3i, 4iv & 4viii) compared to more rounded or truncated in S. pachyarthron (Fig. 11i & 12iii). Identification keys to other species in the area can be found at Simon & Alfonso (2011).

Natural Values (CYNRM, ATH, others)

The species in this genus are collectively referred to as firegrass in Crowley et al (2004) and are considered a critical food source for the Golden Shouldered Parrot. Schizachyrium species produce large amounts of seed which fall to the ground and persist through the dry season. They provide an important food source for many seed-eating specialists before the seeds start to germinate in the early wet season. Although recorded as being grazed by stock they are not considered a valuable fodder species, probably because they offer little in the amount of bulk for grazing stock (Simon 1992, Rolfe 1997, Milson 2000, Lazarides 2002).

Habitat

A common and widespread species from the savanna regions of northern Australia but also recorded from sub-tropical Qld and NSW. Usually collected from sandy soils and often very abundant in local patches (Fig. 13) (Simon & Alfonso 2011). The absence of collections in the lower western quadrant of Cape York Peninsula is likely to be a result of collection effort in that region rather than a true reflection of species distribution (Fig. 14).

Fig. 1. Sheet of pressed herbarium specimen of Schizachyrium fragile (CNS135818).

Resources

AVH (2018) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Council of Heads of Australasian Herbaria, <http://avh.chah.org.au>, accessed 1 Mar 2018.

Blake, S.T. (1974), Revision of the genera Cymbopogon and Schizachyrium (Gramineae) in Australia. Contributions from the Queensland Herbarium 17: 8-14

Crowley, G.M., Garnett, S.T. and Shephard, S. (2004). Management guidelines for golden-shouldered parrot conservation. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Brisbane.

Garnett ST and Crowley GM. 2002. Recovery Plan for the golden-shouldered parrot Psephotus chrysopterygius 2003-2007. Report to Environment Australia, Canberra. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Brisbane.

Hooker, Nanette B. (2016) Grasses of Townsville. James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia.

Lazarides, M. (2002). Economic attributes of Australian grasses. Flora of Australia 43: 213-245.

Milson, J. (2000). Pasture plants of north-west Queensland. Information Series Q100015. Queensland Department of Primary Industries.

Rolfe, J., Golding, T. and Cowan, D. (1997). Is your pasture past it? The glove box guide to native pasture identification in north Queensland. Information Series Q197083. Queensland Department of Primary Industries.

Simon, B.K. in Wheeler, J.R. (ed.) (1992), Schizachyrium. Flora of the Kimberley Region: 1215

Simon, B.K. & Alfonso, Y. (2011) AusGrass2, http://ausgrass2.myspecies.info/accessed on [8 February 2018].