Cape York Peninsula is remote, the northernmost part of Queensland, Australia. It is recognised for its outstanding natural and cultural resources with significant areas identified for future World Heritage listing. The Cape York region is globally significant as one of the last great Wet/Dry tropical systems in the World (Halpern 2008) with relatively intact eastern flowing catchments that feed the World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef and more disturbed western flowing catchments feeding to the Gulf of Carpentaria. It is often referred to as one of the largest unspoilt wilderness areas in the World. Although this is partially true, there are many threats faced by the country and the people of this amazing place. It is certainly relatively intact and has little development compared to many parts of Australia, but it is not devoid of people or management, as wilderness is commonly understood to mean.

Every year large areas of Cape York Peninsula burn at the wrong time, affecting the health and function of the landscape. Many places burn hot that should not and often places that should be protected from fire burn. The impacts of ongoing poor fire management in Cape York are not well studied and extrapolation of the negative effects of poor fire management impacts on the landscape are made from studies in other parts of Australia.

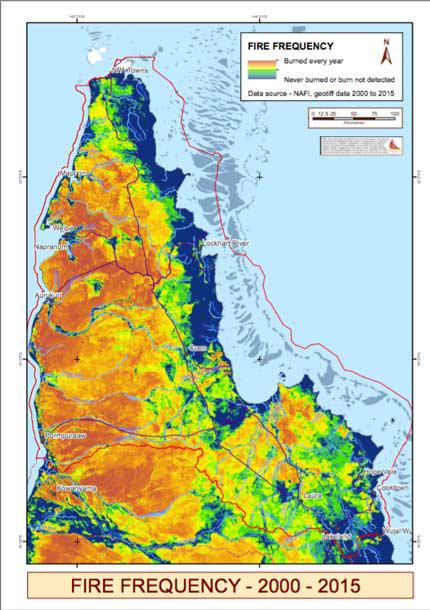

An analysis of fire mapping data from Northern Australia Fire Information site (NAFI) using MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) satellite imagery for Cape York highlights that vast areas of Cape York have high fire frequency, with the majority of areas experiencing fires annually for the past 15 years with little interval between fire events and very few areas of the Cape that experience long unburnt periods.

Climate, seasonal variability and vegetation curing strongly influence fire patterns in Northern Australia. Weather such as rainfall, temperature, wind speed and direction change throughout the day and year and across seasons influencing fire behaviour. Dew point or atmospheric moisture also shifts throughout the day and across seasons and influences fire behaviour and patterns. Soil type and moisture, vegetation type, elevation, time since last burnt which influences fuel loads also change how fires behave throughout the day and night and combined with the characteristics of weather described above are all factors in if and how far a fire will spread.

When (time of day) and how a fire is lit, e.g. using linear or point ignition and/or accelerants will also determine intensity, size, patchiness and the resultant effect on vegetation, soil stability, the capacity of vegetation for evapotranspiration, respiration and photo-synthesis following fire events (Cernusak, Hutley et al. 2006), the amount of greenhouses gases including carbon released into the atmosphere and removed from the site during and following a fire. There is a strong interdependency between fire severity and ecosystem response. People are often heard stating that fire does this or that but it is the type of fire, a complex mix of the characteristics and drivers described that determine what effect fires have on the biotic and abiotic environment.

The wet/dry monsoon season influences fire behaviour in Cape York Peninsula but its effect varies from South to North, East to West (Steffensen 2010, Claudie 2010, Lifu 2015 (pers com), (The State of Queensland Department of National Parks and Racing 2012). As the dry season escalates and vegetation cures prior to the onset of the Monsoon season fire risk increases. At this time of year, anthropogenic causes of fire and frequency of cloud to ground lightning strikes can result in disastrous outcomes, impacting culture, livelihoods and ecosystem function. As the season dries out thousands of square kilometres, anywhere up to three times the area impacted by the 2009 Victorian Bushfires can burn, often extremely hot. Although it is well understood that the majority of fires in Northern Australia are grass fires (Gill 1990, Dunlop and Webb 1991, Haynes, 1991, Crowley 1995) it is less understood that fires at this time of year have a huge impact on the canopy of vegetation, thereby having flow-on influences on the entire ecosystem (Steffensen, Musgrave, George and Standley 2005). For example, canopy scorch and burn result in excessive leaf drop destroying vital habitat and food resources for a myriad of species, transpiration rates of vegetation that assist to regulate climate are impacted, increased heat to ground through loss of the canopy increases soil temperature changing carbon flux in the system (Beringer, Hutley et al. 2003) and influences competition between recruiting species (Crowley and Garnett 1998 ).

Fires at any time of the year, even in the early dry season (EDS) can result in similar effects depending on the multitude of variables that influence fire behaviour described earlier. Early season fires that behave in the same way as a later season wildfire may result in long periods of bare-ground and negative feedback loops on vegetation structure. This is particularly the case if grazing pressure from cattle cannot be managed as this combines with grazing pressure from native species, influencing species composition post-fire events and can increase bare ground for much of the year. Late season wildfires often result in larger areas of bare ground prior to the onset of heavy monsoon wet increasing potential for erosion and sediment movement, decreasing water quality and potentially accelerating gullies where repeated hot fires occur in close proximity to existing gullies.

Analysis of data of fire histories over the past 15 years highlights that the majority of fires have occurred in the last dry and storm season from August to December a result of uncontrollable wildfire.

Although early dry season (EDS) burning is carried out, it has often insufficient to create the breaks required to stop late-season wildfire and areas that have been burnt in the early dry season may re-burn due to the intensity of late-season fire fronts a combination of curing, fuel loads and weather conditions. Looking back over the last 15 years of data reveals that many areas of Cape York are burning repeatedly. Queensland Government fire frequency guidelines recommend that the vegetation types where the majority of this burning is occurring should only burn in the early dry or storm season every 3 – 6 years.

© Standley, P. text provided from “The Importance of Campfires” PhD dissertation. James Cook University

Fire: The Dominant Land Manager

Fire on Cape York is a key threatening process. It impacts on the plants, animals, landscape and health of waterways, wetlands and springs, either positively or negatively.

Aside from lightning strikes that arrive late in the year prior to the onset of the wet season, people start most fires in Cape York, deliberately or by accident. Over the years people have worked hard trying to solve the problem of hot late-season uncontrolled wildfires that can burn up to 70% of Cape York in as little as a few weeks. There is more work to be done; fire management requires constant attention and the involvement of people. As our seasons change, being responsive to fire management requirements requires knowledge and skill.

Storm season burning has been promoted as a management tool for reducing thickening vegetation, particularly broadleaf tea tree suckers (Melaleuca viridiflora). More recently the Savanna Burning methodology is influencing the way people burn, promoting early season burning prior to the carbon abatement cut-off date of 1 August annually. Cape York NRM would like to work with land managers and communities to adjust this methodology so that it better suits our fire management requirements and seasonal shifts.

Like managing most things in the natural environment, fire management is not simple. Satellites don’t see everything – affected by the shape of the Earth, cloud cover, vegetation signals and smoke haze – so fire scar mapping is not an absolute reflection of everything that happens on the ground. Vegetation and animal requirements for fire are diverse and not all systems should be managed the same way to affect a positive result on our biodiversity. Not all vegetation systems are eligible under the savanna burning methodology and so non-eligible vegetation community burn requirements should be considered in overall fire planning and risk mitigation.

Fires behave differently - variability between seasons, time of year, time of day, fuel loads, fine and coarse woody debris, moisture levels, vegetation type, wind patterns, past fire history, known plant and animal species present, aspect, slope, geology, soils, surrounding vegetation communities, on-ground or aerial burning and single, multiple or linear ignition points - all play a role in determining how a fire will or should behave and the impact that it has on our environment.

Cape York NRM supports the Northern Australia Fire Information website via fire scar mapping in partnership with Cape York Sustainable Futures. We have recently developed a prospectus to increase investment in fire management in Cape York. We have developed an updated vegetation base map for Savanna Burning Methodology under the Emission Reduction Fund that improves the detail of vegetation information for people to plan for Savanna Burning 2, in partnership with Firescape Science. A spatial layer is in development for our Atlas to show the burn recommendations for different ecosystems developed by western science for Cape York and to identify gaps in information.

We are planning with properties across Cape York in clusters to develop property and sub-regional implementation plans with land managers (stay tuned; we will be working with you soon if we have not seen you yet). We are working towards updating the regional fire strategy through these clusters to protect our important environmental assets including Cape York’s precious river systems. The edges of waterways and between vegetation communities are important places where plant and animal species can evolve. These areas are also rich in food resources and need to be protected from wildfire.

We support the Indigenous Fire Workshop that has been growing for nine years. The workshop provides people locally and across Australia with skills to help implement, monitor, understand ethnobotany and record fire management. The workshop is a partnership with Mulong’s Victor Steffensen, James Cook University researcher Peta Standley and ethnobotanist Gerry Turpin from the Tropical Herbarium.

We welcome working with all organisations and people with an interest in Cape York’s fire management. We encourage you to contact us to find out more about what we are doing, or to let us know how your fire management projects are going. Contact Cape York NRM on 1300 132 262